26 June 2020

Acacia Pepler, Bureau of Meteorology

Acacia contributes towards ESCC Hub Project 5.5: Extreme weather hazards in a changing climate

During 2019, Australia recorded its driest year on record. Many different factors contributed to the dry weather, including a strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole during the second half of the year. But if you were watching the weather charts, you might have noticed something curious – the low pressure systems we are used to seeing over southern Australia just didn’t seem to be coming as often as they should.

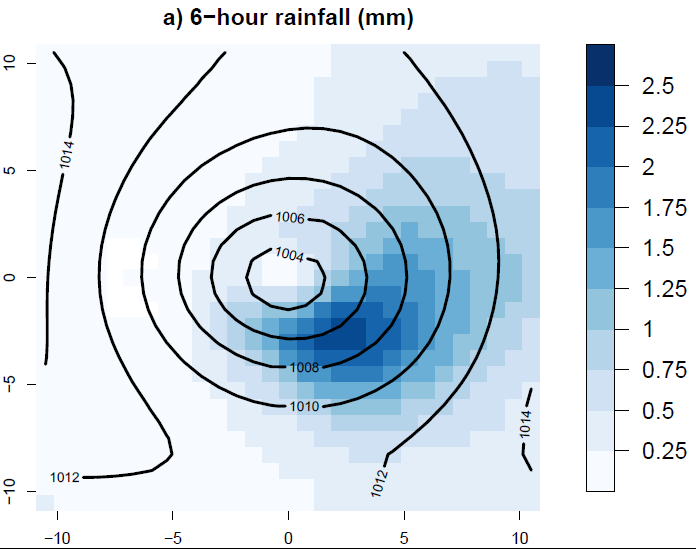

Low pressure systems (or ‘lows’) are a familiar sight on our daily weather charts. A low is an area where the atmospheric pressure is lower than the surrounding environment, and the winds circle in a clockwise (‘cyclonic’) direction into the centre of the low. This leads to rising air and rainfall, especially on the southern and eastern sides of the low. Lows can often produce very heavy rainfall across southern Australia, particularly during the cooler half of the year when they are responsible for a large proportion of our rainfall, and severe lows such as ‘East Coast Lows’ can also cause strong winds, large waves, coastal erosion, and even tornadoes! Lows are also very important in northern Australia during the warmer half of the year, especially the severe lows known as Tropical Cyclones.

Figure 1: The average low in southeast Australia. Black lines show contours of sea level pressure, with lower pressure in the centre of the low, and blue shading shows the average rainfall within 6 hours.

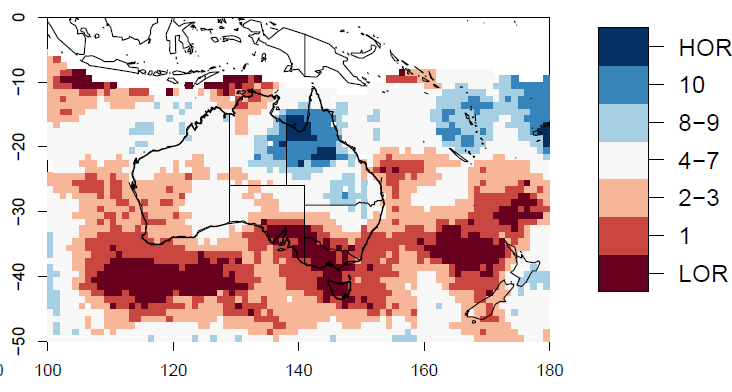

New Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub research published in Geophysical Research Letters shows that the number of lows in southern Australia during 2019 was about half the number we expect in a normal year and the fewest recorded in at least 50 years. The number of lows was also very low during 2018, which had the fewest lows on record for the east coast. In contrast, parts of northern Queensland had more lows than normal, predominantly due to a persistent monsoonal low over 27 Jan-8 Feb that caused prolonged heavy rain and flooding.

Figure 2: Number of lows in 2019, shown as a decile rank compared to all other years 1979-2019. Areas in dark red had the fewest lows on record, and lighter red (decile 1) indicates where the number of lows was in the lowest 10% of years.

At the same time, the number of high pressure systems passing through southern Australia was well above average, especially between April and September. The opposite of lows, highs are areas where the atmospheric pressure is higher than the surrounding environment. Underneath the high, air slowly descends to the surface, bringing dry, clear conditions.

Figure 3: Number of highs in 2019, shown as a decile rank compared to all other years 1979-2019. Areas in dark red had the most highs on record, and lighter red (decile 10) indicates where the number of highs was in the highest 10% of years.

Over the past 50 years, the frequency of highs has been increasing in southern Australia, which has contributed to declining cool season rainfall in parts of southeast Australia. The number of lows has also been decreasing, particularly during the cool half of the year, although the number of lows varies a lot from year to year.

Climate models project that cool season rainfall in parts of southeast and southwest Australia will continue to decrease into the future, and that the average pressure over Australia will continue to increase. The number of low pressure systems is also projected to decline, including the number of East Coast Lows.

Researchers in the Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub are continuing to improve understanding of trends in rainfall, lows and east coast lows and how they may change into the future. This information will provide reliable and relevant information for input into planning and management activities by Australian sectors, communities and ecosystem managers.