16 September 2019

Jess Melbourne-Thomas, Kathleen McInnes, Nathan Bindoff and Nerilie Abram

Co-authors Dr Kathy McInnes and Professor Nathan Bindoff are researchers in Hub projects 5.8 and 5.7.

Research from across multiple Hub projects was used to inform the findings of the report.

Discussions on how to address climate change have focused, very appropriately, on reducing greenhouse gas emissions,

A landmark scientific report has confirmed that climate change is altering the world’s seas and ice at an unprecedented rate. Australia depends on the ocean that surrounds us for our health and prosperity. So what does this mean for us, and life on Earth?

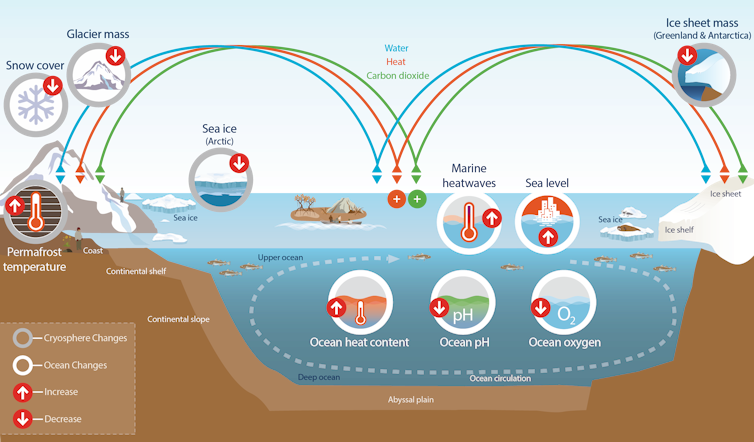

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) findings were launched in Monaco on Wednesday night. They provide the most definitive scientific evidence yet of warmer, more acidic and less productive seas. Glaciers and ice sheets are melting, causing sea level to rise at an accelerating rate.

The implications for Australia are serious. Extreme sea level events that used to hit once a century will occur once a year in many of the world’s coastal places by 2050. This situation is inevitable, even if greenhouse gas emissions are dramatically curbed.

The findings, titled the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, strengthen the already compelling case for countries to meet their emission reduction goals under the 2015 Paris agreement.

Joel Carrett/AAP

Read more: ‘This situation brings me to despair’: two reef scientists share their climate grief

A rapid and dramatic cut in greenhouse gas emissions would prevent the most catastrophic damage to the ocean and cryosphere (frozen polar and mountain regions). This would help protect the ecosystems and people that rely on them.

The report entailed two years of work by 104 authors and review editors from 36 countries, who assessed nearly 7,000 scientific papers and responded to more than 30,000 review comments.

The picture is worse than we thought

Mountain glaciers and polar ice sheets are shrinking and, together with expansion of the warming ocean, are contributing to an increasing rate of sea level rise.

During the last century, global sea levels rose about 15cm. Seas are now rising more than twice as fast – 3.6mm per year – and accelerating, the report shows.

The IPCC’s projections are more dire than in its 2014 oceans report. It has revised upwards by 10% the effect of the melting Antarctic ice sheet on sea level rise by 2100. Antarctica appears to be changing more rapidly than was thought possible even five years ago, and further work is needed to understand just how quickly ice will be lost from Antarctica in future.

IPCC, 2019

If you live near the Australian coast, change is coming

By 2050, more than one billion of the world’s people will live on coastal land less than 10 metres above sea level. They will be exposed to combinations of sea level rise, extreme winds, waves, storm surges and flooding from intensified storms and tropical cyclones.

Many of Australia’s coastal cities and communities can expect to experience what was previously a once-in-a-century extreme coastal flooding event at least once every year by the middle of this century.

Our island neighbours in Indonesia and the Pacific will also be hit hard. The report warns that some island nations are likely to become uninhabitable – although the extent of this is hard to assess accurately.

Some change is inevitable and we will have to adapt. But the report also delivered a strong message about the choices that still remain. In the case of extreme sea level events around Australia, we believe a marked global reduction in greenhouse as emissions would buy us more than 10 years of extra time, in some places, to protect our coastal communities and infrastructure from the rising ocean.

MAST IRHAM/EPA

More frequent extreme events are often occurring at the same time or in quick succession. Tasmania’s summer of 2015-16 is a good example. The state experienced record-breaking drought which worsened the fire threat in the highlands. An unprecedented marine heatwave along the east coast damaged kelp forests and caused disease and death of shellfish, and the state’s northeast suffered severe flooding.

This string of events stretched emergency services, energy supplies and the aquaculture and manufacturing industries. The total economic cost to the state government was an estimated A$445 million. The impacts on the food, energy and manufacturing sectors cut Tasmania’s anticipated economic growth by about half.

Reefs and fish stocks are suffering

The ocean has taken a huge hit from climate change – taking up heat, absorbing carbon dioxide that makes the water more acidic, and losing oxygen. It will bring ocean conditions unlike anything we have seen before.

Marine ecosystems and fisheries around the world are under pressure from this barrage of stressors. Overall, the fisheries potential around Australia’s coasts is expected to decline during this century.

Heat build-up in the surface ocean has already triggered a marked rise in the intensity, frequency and duration of marine heatwaves. Ocean heatwaves are expected to become between four and ten times more common this century, depending on how rapidly global warming continues.

Read more: Extreme weather caused by climate change has damaged 45% of Australia’s coastal habitat

Our choices now are critical for the future

This report reinforces the findings of earlier reports on the importance of limiting global warming warming to 1.5℃ if we are to avoid major impacts on the land, the ocean and frozen areas.

Even if we act now to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, some damage is already locked in and our ocean and frozen regions will continue to change for decades to centuries to come.

Australian Antarctic Division

In Australia, we will need to adapt our coastal cities and communities to unavoidable sea level rise. There are a range of possible options, from building barriers to planned relocation, to protecting the coral reefs and mangroves that provide natural coastal defences.

But if we want to give adaptation the best chance of working, the clear message of this new report is that we need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible.![]()

Jess Melbourne-Thomas, Transdisciplinary Researcher & Knowledge Broker, CSIRO; Kathleen McInnes, Senior research scientist, CSIRO; Nathan Bindoff, Professor of Physical Oceanography, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, and Nerilie Abram, ARC Future Fellow, Research School of Earth Sciences; Chief Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.