11 September 2017

On average, global sea level has risen over 20 cm since the late 19th century and it continues to rise at around 3.3 mm/year. However, the rise is not uniform. It varies from year to year and place to place due to the natural variability of the climate system. Satellite observations since 1993 show that sea-level rise rates on the central east and southern coasts of Australia have been in line with the global average, while rates are higher to the north, west and south-east of the continent.

As sea levels rise, the effects of high tides and storm surges are becoming greater. These effects also vary from place to place, and Australia’s extensive coastline experiences extreme sea levels from a variety of tropical to mid-latitude weather systems, each of which themselves may be affected differently by climate change.

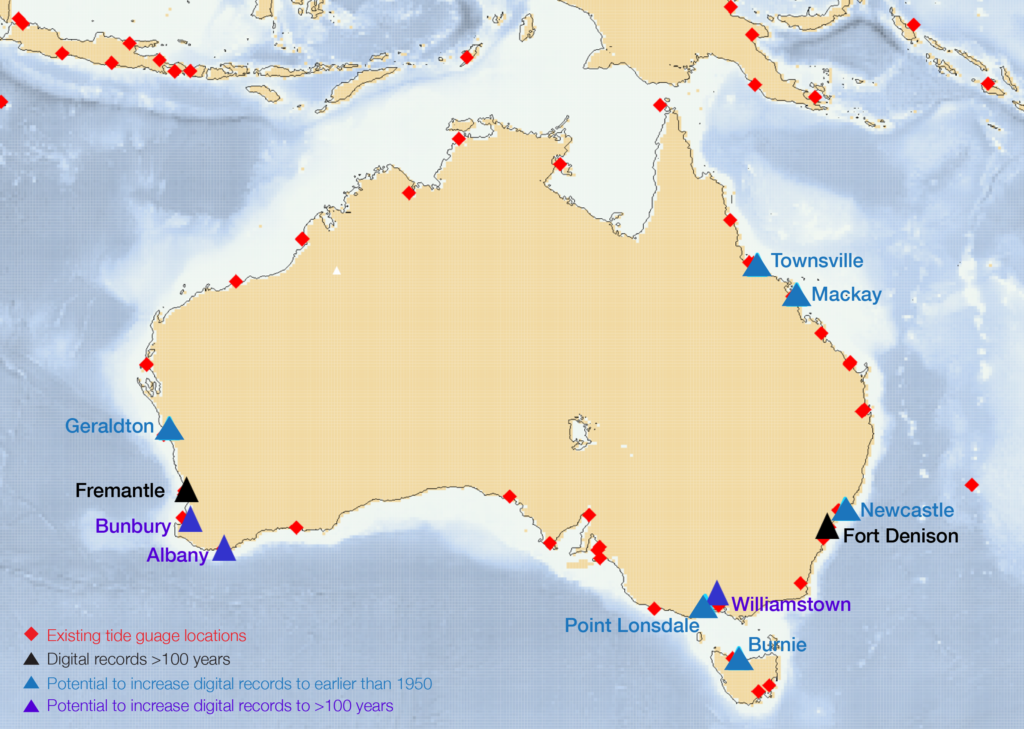

Long-term tide records of high temporal (e.g. hourly) resolution allow us to not only better understand how mean sea level has changed in the past but also understand how extreme sea levels such as storm surges have changed along with the weather systems that cause them. A greater understanding of past change builds confidence in projections of future change. At present, Australia has only two such records available digitally – Fort Denison, Sydney (with data from 1912) and Fremantle, Perth (with data from 1880). Other long-term records exist, but the data is recorded in old charts (marigrams) and books and so is unavailable for modelling and analysis.

Unlocking old data

A Hub project is underway to digitise these old hard-copy records so the data they contain can be used to analyse how extreme sea levels in Australia have changed over time.

Undigitised tide records are available for Newcastle (NSW), Mackay and Townsville (Qld), Point Lonsdale and Williamstown (Vic), Burnie (Tas) and Albany, Bunbury and Geraldton (WA).

The Williamstown record is the first cab off the rank for digitisation for a number of reasons. As well as having marigrams that extend back the furthest (to 1875), Williamstown has a near-complete set of tide registers (books containing the measured daily high and low waters) from 1872.

Williamstown’s location on the south coast also means it is exposed to different meteorological causes of extreme sea levels, so tide information from here can increase our understanding of the local surge-generating storm systems.

Historical sources

The Williamstown marigrams record tide data from 1875 until 1965 when the digital record began (although the charts from 1946–1949 are missing). In total, there are around 22,000 charts to be digitised.

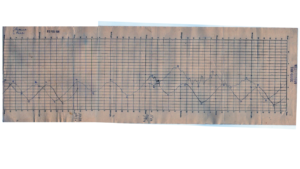

The format of the charts differs through time. For the most recent records (1950–1965), chart paper covering four days was used with two charts covering a week.

From 1926-1945, the same chart type was used but was kept on the gauge for the full week resulting in two overlapping curves.

Prior to 1926, a single chart was used each day.

The marigram data is complemented by two other sources of data from the Port of Melbourne Authority.

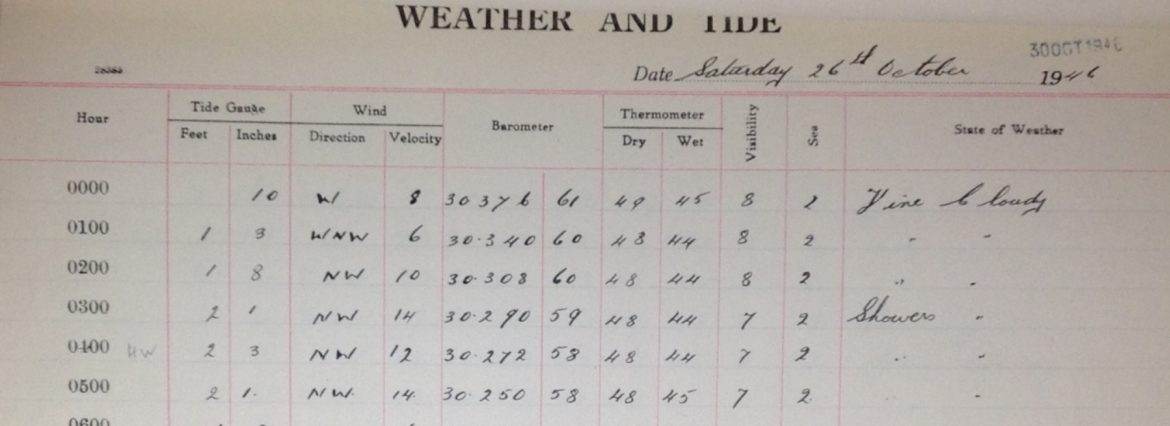

The first is a series of books containing daily high and low water levels from 1872 through to the mid-1970s (except for a gap from September 1940 to August 1943). The second source is a set of books containing hourly tide and weather observations from September 1943 to December 1948 taken at Williamstown’s Breakwater Pier. These records provide an additional source of data to infill gaps in the marigrams due to faults in the tide gauge or damaged or missing marigrams. The registers also provide additional metadata.

Getting down to digitising

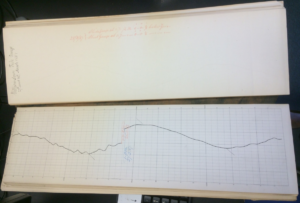

Translating these charts into digital data is a time-consuming business. Each marigram is scanned and digitisation software used to click along the trace representing water level to convert it into a digital record. The data is converted to the relevant vertical height datum graphed and checked for errors before being further processed and interpolated to a regular time interval. The data from the tide registers and tide and weather books are entered into spreadsheets. Due to the nature of the old records, these activities cannot be automated and all have to be carried out by hand.

To date, the marigrams for 1950–1965 have been digitised and are undergoing quality checking, and work is now underway on records from the 1940s. However, with around 19,000 charts still to be digitised, there’s still a lot of work to do.

Get involved!

Much of the digitisation to this point has been carried out by a small team of student volunteers – but we need more people power to digitise the remaining charts.

Digitising the records is not difficult, but does require attention to detail and some preliminary training from our sea-level researchers.

If you have a reliable internet connection, access to Microsoft Excel (and you are familiar with using it), an interest in understanding our changing climate and some time to spare, please get in touch with Kathy McInnes or Claire Trenham to find out more.

Digitisation of historical tide records is being carried out through Project 2.10: Coastal hazards in a variable and changing climate.