4 December 2019

Pep Canadell, Corinne Le Quéré, Glen Peters, Pierre Friedlingstein, Robbie Andrew, Rob Jackson, and Vanessa Haverd.

Pep Canadell and Vanessa Haverd contribute to ESCC Hub Project 5.6.

Global emissions for 2019 are predicted to hit 36.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂), setting yet another all-time record. This disturbing result means emissions have grown by 62% since international climate negotiations began in 1990 to address the problem.

The figures are contained in the Global Carbon Project, which today released its 14th Global Carbon Budget.

Read more: Eighteen countries showing the way to carbon zero

Digging into the numbers, however, reveals a silver lining. While overall carbon emissions continue to rise, the rate of growth is about two-thirds lower than in the previous two years.

Driving this slower growth is an extraordinary decline in coal emissions, particularly in the United States and Europe, and growth in renewable energy globally.

A less positive component of this emissions slowdown, however, is that a lower global economic growth has contributed to it. Most concerning yet is the very robust and stable upward trends in emissions from oil and natural gas.

Coal is king, but losing steam

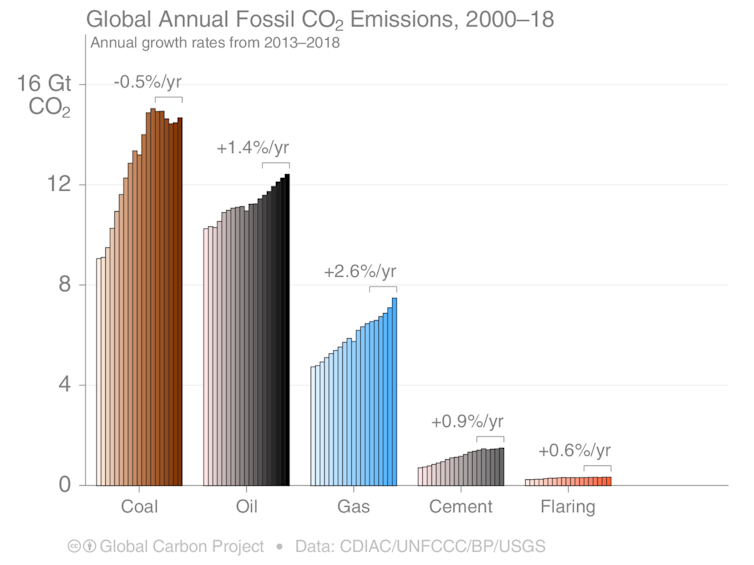

The burning of coal continues to dominate CO₂ emissions and was responsible for 40% of all fossil fuel emissions in 2018, followed by oil (34%) and natural gas (20%). However, coal emissions reached their highest levels in 2012 and have remained slightly lower since then. Emissions have been declining at an annual average of 0.5% over the past five years to 2018.

Global Carbon Project 2019

In 2019, we project a further decline in global coal CO₂ emissions of around 0.9%. This decline is due to large falls of 10% in both the US and the European Union, and weak growth in China (0.8%) and India (2%).

The US has announced the closure of more than 500 coal-fired power plants over the past decade, while the UK’s electricity sector has gone from 40% coal-based power in 2012 to 5% in 2018.

Whether coal emissions reached a true peak in 2012 or will creep back up will depend largely on the trajectory of coal use in China and India. Despite this uncertainty, the strong upward trend from the past has been broken and is unlikely to return.

Oil and natural gas grow unabated

CO₂ emissions from oil and natural gas in particular have grown robustly for decades and show no signs of slowing down. In fact, while emissions growth from oil has been fairly steady over the past decade at 1.4% a year, emissions from natural gas have grown almost twice as fast at 2.4% a year, and are estimated to further accelerate to 2.6% in 2019. Natural gas is the single largest contributor to this year’s increase in global CO₂ emissions.

This uptick in natural gas consumption is driven by a range of factors. New, “unconventional” methods of extracting natural gas in the US have increased production. This boom is in part replacing coal for electricity generation.

Read more: How to answer the argument that Australia’s emissions are too small to make a difference

In Japan, natural gas is filling the void left by nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster. In most of the rest of the world, new natural gas capacity is primarily filling new energy demand.

Oil emissions, on the other hand, are largely being driven by the rapidly growing transport sector. This is increasing across land, sea and air, but is dominated by road transport.

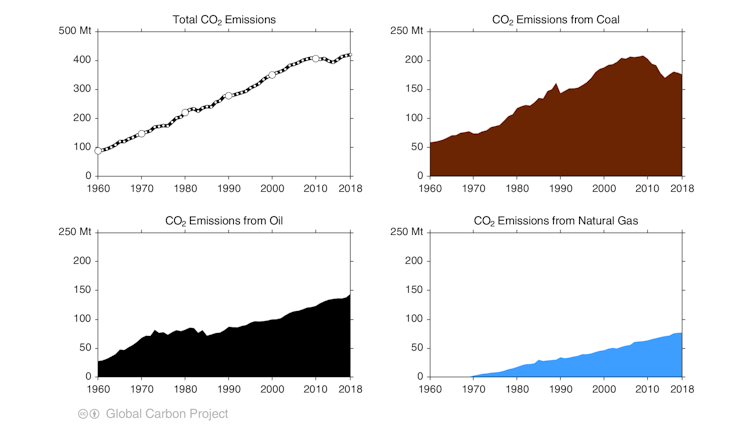

Australia’s emissions have also seen significant reductions from coal sources over the past decade, while emissions from oil and natural gas have grown rapidly and are driving the country’s overall growth in fossil CO₂ emissions.

Data Source: UNFCCC, CDIAC, BP, USGS

Emissions from deforestation

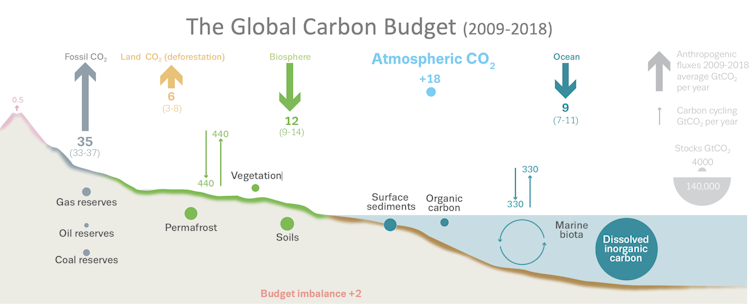

Preliminary estimates for 2019 show that global emissions from deforestation, fires and other land-use changes reached 6 billion tonnes of CO₂ – about 0.8 billion tonnes above 2018 levels. The additional emissions largely come from elevated fire and deforestation activity in the Amazon and Southeast Asia.

The accelerated loss of forests in 2019 not only leads to higher emissions, but reduces the capacity of vegetation to act as a “sink” removing CO₂ from the atmosphere. This is deeply concerning, as the world’s oceans and plants absorb about half of all CO₂ emissions from human activities. They are one of our most effective buffers against even higher CO₂ concentrations in the atmosphere, and must be safeguarded.

Global Carbon Project 2019

Not all sinks can be managed by people – the open ocean sink being an example – but land-based sinks can be actively protected by preventing deforestation and degradation, and further enhanced by ecosystem restoration and reforestation.

Read more: Climate explained: what each of us can do to reduce our carbon footprint

For every year in which global emissions grow, the goals of the Paris Agreement are one step further removed from being achievable. We know many ways to decarbonise economies that are good for people and the environment. Some countries are showing it is possible. It is time for the rest of the world to join them.![]()

Pep Canadell, Chief research scientist, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere; and Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor, University of East Anglia, University of East Anglia; Glen Peters, Research Director, Center for International Climate and Environment Research – Oslo; Pierre Friedlingstein, Chair, Mathematical Modelling of Climate, University of Exeter; Robbie Andrew, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research – Oslo; Rob Jackson, Chair, Department of Earth System Science, and Chair of the Global Carbon Project, globalcarbonproject.org, Stanford University, and Vanessa Haverd, Senior research scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.