Pep Canadell, CSIRO; Eric Davidson, University of Maryland, Baltimore; Glen Peters, Center for International Climate and Environment Research – Oslo; Hanqin Tian, Auburn University; Michael Prather, University of California, Irvine; Paul Krummel, CSIRO; Rob Jackson, Stanford University; Rona Thompson, Norwegian Institute for Air Research, and Wilfried Winiwarter, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

Nitrous oxide from agriculture and other sources is accumulating in the atmosphere so quickly it puts Earth on track for a dangerous 3℃ warming this century, our new research has found.

Each year, more than 100 million tonnes of nitrogen are spread on crops in the form of synthetic fertiliser. The same amount again is put onto pastures and crops in manure from livestock.

This colossal amount of nitrogen makes crops and pastures grow more abundantly. But it also releases nitrous oxide (N₂O), a greenhouse gas.

Agriculture is the main cause of the increasing concentrations, and is likely to remain so this century. N₂O emissions from agriculture and industry can be reduced, and we must take urgent action if we hope to stabilise Earth’s climate.

Where does nitrous oxide come from?

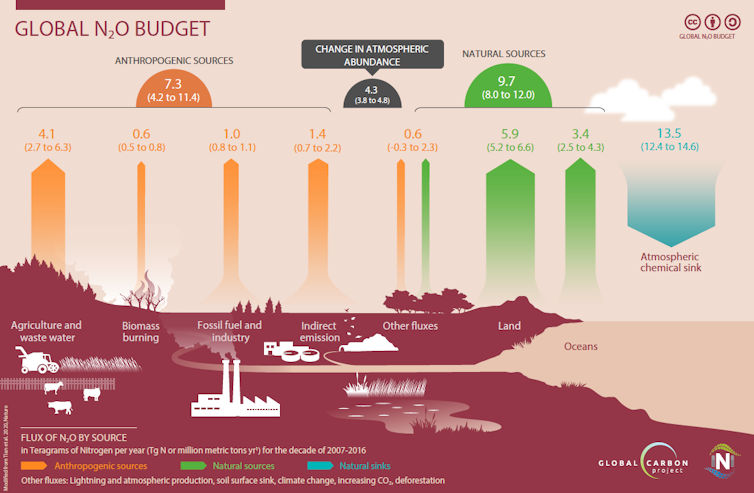

We found that N₂O emissions from natural sources, such as soils and oceans, have not changed much in recent decades. But emissions from human sources have increased rapidly.

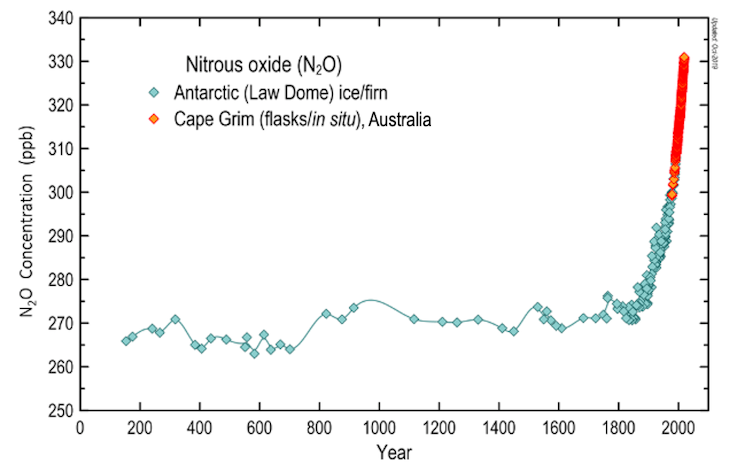

Atmospheric concentrations of N₂O reached 331 parts per billion in 2018, 22% above levels around the year 1750, before the industrial era began.

Agriculture caused almost 70% of global N₂O emissions in the decade to 2016. The emissions are created through microbial processes in soils. The use of nitrogen in synthetic fertilisers and manure is a key driver of this process.

Other human sources of N₂O include the chemical industry, waste water and the burning of fossil fuels.

N₂O is destroyed in the upper atmosphere, primarily by solar radiation. But humans are emitting N₂O faster than it’s being destroyed, so it’s accumulating in the atmosphere.

N₂O both depletes the ozone layer and contributes to global warming.

As a greenhouse gas, N₂O has 300 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and stays in the atmosphere for an average 116 years. It’s the third most important greenhouse gas after CO₂ (which lasts up to thousands of years in the atmosphere) and methane.

N₂O depletes the ozone layer when it interacts with ozone gas in the stratosphere. Other ozone-depleting substances, such as chemicals containing chlorine and bromine, have been banned under the United Nations Montreal Protocol. N₂O is not banned under the protocol, although the Paris Agreement seeks to reduce its concentrations.

Shutterstock

What we found

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has developed scenarios for the future, outlining the different pathways the world could take on emission reduction by 2100. Our research found N₂O concentrations have begun to exceed the levels predicted across all scenarios.

The current concentrations are in line with a global average temperature increase of well above 3℃ this century.

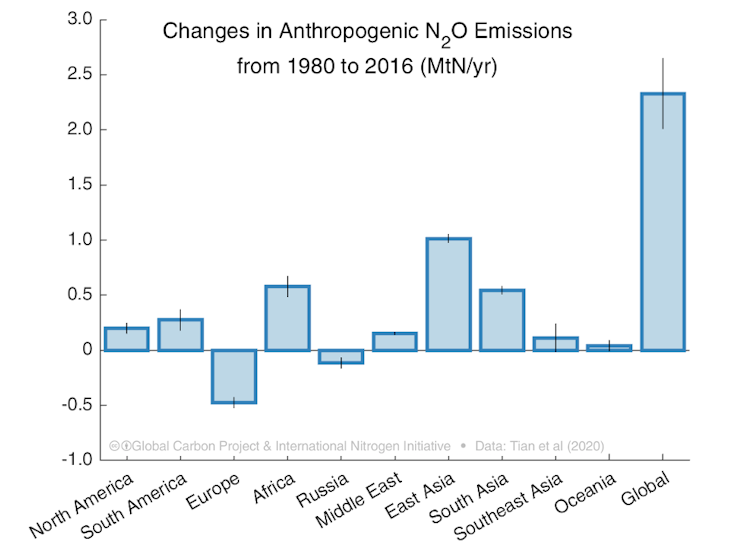

We found that global human-caused N₂O emissions have grown by 30% over the past three decades. Emissions from agriculture mostly came from synthetic nitrogen fertiliser used in East Asia, Europe, South Asia and North America. Emissions from Africa and South America are dominated by emissions from livestock manure.

In terms of emissions growth, the highest contributions come from emerging economies – particularly Brazil, China, and India – where crop production and livestock numbers have increased rapidly in recent decades.

N₂O emissions from Australia have been stable over the past decade. Increase in emissions from agriculture and waste have been offset by a decline in emissions from industry and fossil fuels.

What to do?

N₂O must be part of efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and there is already work being done. Since the late 1990s, for example, efforts to reduce emissions from the chemicals industry have been successful, particularly in the production of nylon, in the United States, Europe and Japan.

Reducing emissions from agriculture is more difficult – food production must be maintained and there is no simple alternative to nitrogen fertilisers. But some options do exist.

Read more:

Emissions of methane – a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide – are rising dangerously

In Europe over the past two decades, N₂O emissions have fallen as agricultural productivity increased. This was largely achieved through government policies to reduce pollution in waterways and drinking water, which encouraged more efficient fertiliser use.

Other ways to reduce N₂O emissions from agriculture include:

- better management of animal manure

- applying fertiliser in a way that better matches the needs of growing plants

- alternating crops to include those that produce their own nitrogen, such as legumes, to reduce the need for fertiliser

- enhanced efficiency fertilisers that lower N₂O production.

Getting to net-zero emissions

Stopping the overuse of nitrogen fertilisers is not just good for the climate. It can also reduce water pollution and increase farm profitability.

Even with the right agricultural policies and actions, synthetic and manure fertilisers will be needed. To bring the sector to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, as needed to stabilise the climate, new technologies will be required.

Pep Canadell contributes to ESCC Hub Project 5.6.

Read more:

Earth may temporarily pass dangerous 1.5℃ warming limit by 2024, major new report says

Pep Canadell, Chief research scientist, Climate Science Centre, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere; and Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Eric Davidson, Director, Appalachian Laboratory and Professor, University of Maryland, Baltimore; Glen Peters, Research Director, Center for International Climate and Environment Research – Oslo; Hanqin Tian, Director, International Center for Climate and Global Change Research, Auburn University; Michael Prather, Distinguished Professor of Earth System Science, University of California, Irvine; Paul Krummel, Research Group Leader, CSIRO; Rob Jackson, Professor, Department of Earth System Science, and Chair of the Global Carbon Project, Stanford University; Rona Thompson, Senior scientist, Norwegian Institute for Air Research, and Wilfried Winiwarter, , International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.