29 April 2021

Acacia Pepler, Bureau of Meteorology

Acacia contributes towards ESCC Hub Project 5.5: Extreme weather hazards in a changing climate

Cyclones are large-scale air masses that rotate clockwise (in the Southern Hemisphere) around a strong centre of low atmospheric pressure. They are often accompanied by strong winds, heavy rain and large waves. While tropical cyclones develop over the warmer waters to the north of Australia, extratropical cyclones are an important source of rainfall in southern Australia and the extratropics of the globe.

Extratropical cyclones can be categorised in many different ways. One useful way is based on their vertical structure. The ‘deep’ cyclones that cause the heaviest rainfall extend kilometres up into the atmosphere. In comparison, ‘shallow’ cyclones that are only apparent close to the surface, or only higher in the atmosphere, are much less likely to cause heavy rain. This result is true for the East Coast Lows that influence the Australian east coast, but new research shows that it is also true for most of the globe.

Frequency of deep and shallow cyclones under a warming climate

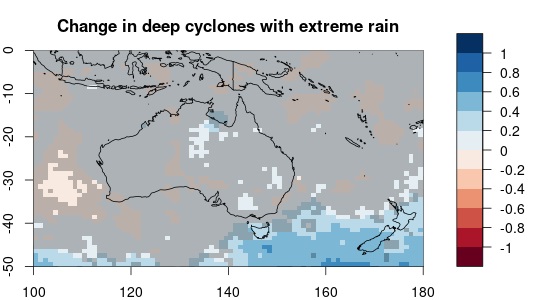

Unfortunately, these deep cyclones are also the most sensitive to our changing climate. Under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5), climate models project a 20% decline in deep cyclones across the Southern Hemisphere subtropics (15-45°S) by the late 21st Century. For southern Australia, the mean decline is 26%. At the same time, shallow surface cyclones are likely to become more common, especially over land areas during the summer.

Figure 1: ‘Deep’ cyclones are projected to decline while ’shallow’ cyclones are projected to increase under a high emissions scenario. Percentage change in deep cyclones and shallow surface cyclones between 1979-2005 and 2070-2099 under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5), averaged over 10 CMIP5 models. Grey shading indicates where fewer than 8/10 models agree on the direction of the change and hence confidence is lower.

Change in cyclone related rainfall under a warming climate

Since deep cyclones produce more rainfall, this change in cyclone frequency also means a change in the total rainfall from cyclones in the future, especially during the cool season. This plays an important role in projected rainfall declines in areas like southern Australia.

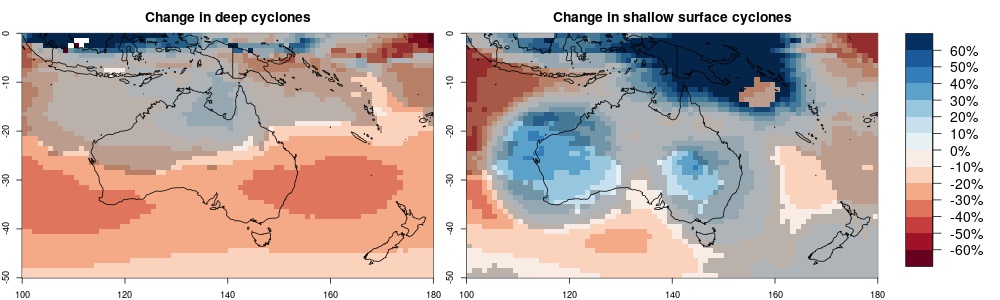

However, in a warming world, the air can hold a lot more moisture. While deep cyclones are becoming less frequent, in a warmer world the most intense deep cyclones can produce a lot more rain. This means that in many parts of the world the frequency of extreme rainfall due to deep cyclones is likely to stay the same or increase, even in places where the overall cyclone frequency and rainfall totals go down.

This includes southern Australia, where despite the projected declines in deep cyclone frequency there are no indications of a decline in associated heavy rain days. In fact, averaged across southern Australia the number of heavy rain days from deep cyclones is likely to increase, particularly around Tasmania.

Figure 2: The frequency of extreme rainfall due to deep cyclones is likely to stay the same or increase. Average number of additional extreme rain days (equal to the current wettest day per year) in 2070-2099 across 10 CMIP5 models.

A future world with fewer of the cyclones that produce heavy rainfall, no change or an increase in the heaviest rain events, could have serious implications for both water security and floods in many parts of Australia, especially on the east coast.

Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub researchers have worked to better understand future changes in the types of cyclones that matter most in southern Australia, helping to better plan for changes in our rainfall and water systems.

Read the recently published ESCC Hub paper: Pepler A and Dowdy A. 2021. Fewer deep cyclones projected for the midlatitudes in a warming climate, but with more intense rainfall. Environmental Research Letters, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abf528.